Investigating the Nunatsiavut Textile Tradition

May 18, 2022

by Genevieve LeMoine and Susan A. Kaplan

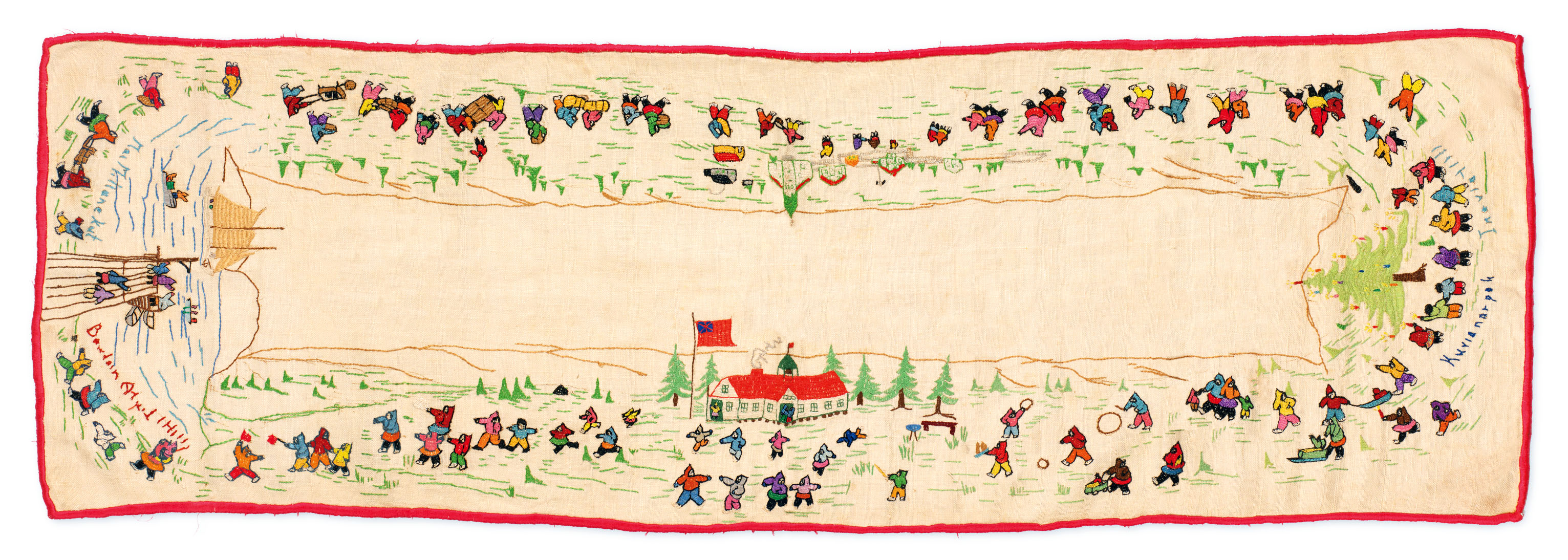

As we unfolded an embroidered table runner on a desk in the Nunatsiavut Government building in Nain, Nunatsiavut, NL, attendees of our open house leaned forward, eager to see what scenes were depicted on the textile. They saw inukuluit (singular: inukuluk)—tiny figures dressed in brightly coloured parkas, running hand in hand, picking berries, searching for robins’ eggs and feeding a fire for a boil-up. Some inukuluit wave to a schooner in the distance or play with a ball, while others hunt butterflies. As they had done in other Nunatsiavut communities we visited, people remarked on the skill and time required to produce these unusual textiles.

We were in Nunatsiavut to learn more about this embroidery tradition, now practiced by fewer and fewer women. [1] We had twenty-four domestic textiles with us, selected from the nearly 100 pieces in the collection of the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. They were given to, or purchased by, American Arctic explorer Donald B. MacMillan and his wife Miriam MacMillan on their many trips along the Labrador coast in the schooner Bowdoin between 1921 and 1954. The MacMillans donated these works to the Arctic Museum where they have lain, unstudied, for over 50 years.

The Arctic Museum’s records reveal that Nunatsiavummiut women and girls had embroidered the inukuluit on tablecloths, napkins and other domestic textiles in the middle decades of the twentieth century. We also understood that Kate Hettasch, daughter of Moravian missionaries in Labrador, taught embroidery in Labrador schools and created some of the designs featured on the embroideries. Beyond this, however, we knew little about them. We have found only scattered examples of similar embroideries in other museums and archives, and few published references to them. Judy McGrath described them in the catalogue for the 1985 exhibit Labrador Crafts Past and Present at the Memorial University of Newfoundland Art Gallery. More recently, art historian Dr. Heather Igloliorte has discussed how seamstresses transferred this style of embroidery to clothing. We were left with many unanswered questions, and we hoped that by bringing community members and the embroideries together we could all better understand who created the designs, who did the embroidery and the contexts in which these interesting textiles were produced.

The project sprung from the 2014 Heritage Forum in Nain where Susan A. Kaplan showed photographs of the embroideries in a presentation highlighting Labrador-related materials in the Arctic Museum collection. A subsequent survey about potential research topics revealed that Nunatsiavummiut were very interested in learning more about them.

In the spring of 2018 we travelled to Nain with photographs of all the pieces in our collection to talk with community members about how we should proceed. The message they had for us was clear: photographs, no matter how good, would not do. To understand the pieces they needed to see the embroideries themselves. Under the guidance of a textile conservator, we packed two-dozen textiles and visited four Nunatsiavut communities in the Spring of 2019, holding open houses and one-on-one interviews so more people could see them first hand.

We had many fundamental questions about the embroideries. We wondered about the nature of the authorship of the patterns, how collaborative was the embroidery of the larger pieces and how were materials obtained. We also had questions about how women learned to embroider and the social and economic contexts of their work. Most importantly, we wanted to listen and understand what the community had to say about these textiles.

We learned that what we initially took to be generic backgrounds behind the inukuluit were in fact identifiable landscape features, such as Mount Sophia in Nain. Buildings were also depicted in detail: most often the distinctive Moravian church in Nain, the schoolhouse and in one case the neighbourhood around the Nain mission, complete with fenced gardens. Elders even named the families who had lived in each house, although the houses themselves are long gone.

In this familiar landscape, inukuluit perform routine chores such as fetching water or carrying supplies from the pier to the school. Others carry small spruce trees, Advent gifts for their godmothers or simply walk hand-in-hand to church. The attention to detail evident in these works is remarkable, as is the craftsmanship. Stitches are tiny and even, and close attention is paid to colour schemes. While most of the figures are done in satin with stem stitches, scenes are framed by a border created using one of a variety of stitches.

One tablecloth that consistently drew attention in our open houses was the sole piece with a cohesive narrative, depicting a polar bear hunt. It follows two men who leave their cabin to track a bear to a rocky shore where they shoot it, load it on a komatik and mush it home. As with all the embroideries, tiny details matter. The trajectories of the bullets are embroidered, as is the small red wound where the bullet hit its mark.

When we visited the White Elephant Museum in Makkovik, Nunatsiavut, NL, historian Joan Anderson recognized this story and showed us a 1960 photograph of Kate Hettasch and Joan Cotton, both teachers at the local school, holding up a nearly identical version, troubling any hypotheses of authorship we were building. She brought out an illustrated book by another local teacher, Doris Peacock—featuring the story of a boy’s first polar bear hunt near Nain. Her illustrations for that story are similar to the embroidered scenes—could they be telling the same story? Might the embroidery pattern be based on Peacock’s book? The origins are even more complex perhaps, as shortly after the museum’s tablecloth was featured on CBC News, we heard from an archivist at the Rooms in St John’s, NL, who had recently catalogued a nearly identical pattern that had been donated by a former Grenfell nurse. Based on many stories of lengthy stays in Grenfell hospitals by north coast residents, we now suspect there were considerable back and forth influences as women moved between Moravian and Grenfell institutions, further complicating the question of authorship of individual works.

So far, no one has been able to tell us who might have embroidered any of our pieces, and some have suggested that we might be too late; the elders who would have recognized their own handiwork have passed away. We still hold out some hope, however. In upcoming visits we will expand our study and visit institutions that have collections of embroidery patterns. We hope through the patterns we can learn more about the authorship of these pieces and the contexts in which these embroideries were made.

There’s still much to learn from these cheerfully embroidered scenes of inukuluit. As we move forward in our work with community members, we are excited about the possibility of sharing these pieces more broadly in two ways: by developing a travelling exhibit or publication featuring the Arctic Museum’s collection, and fostering a larger, public conversation by publishing detailed images on Facebook. [2] We understand it’s crucial to investigate these threads together, supporting the renewed interest in this distinct textile tradition among generations of Nunatsiavummiut women. Talented makers from the region elaborate on this tradition. Celebrated fibre artist Shirley Moorhouse, whose wall hangings are included in The Rooms Provincial Art Collection and the Indigenous Art Collection, and younger textile artists Inez Shiwak, Chantelle Andersen and others, incorporate new materials, new narratives and mimetic techniques. It is our hope that by making the textiles in our collection widely available, the history, skill and culture carried within them can continue to inspire new artistic directions.

NOTES

1 This project was funded by Kane Lodge Foundation, Inc. and Tradition + Transition, a partnership between the Nunatsiavut Government and Memorial University of Newfoundland with funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Work was conducted under a permit from the Nunatsiavut Government.

2 Visit facebook.com/nunatsiavutembroideries to learn more.

This Legacy was first published in the Spring 2020 issue of the Inuit Art Quarterly.