Goota Ashoona Created One of the Largest Inuit Sculptures in the World for WAG Qaumajuq

Inuit Art Foundation | January 21, 2021

Categories: news

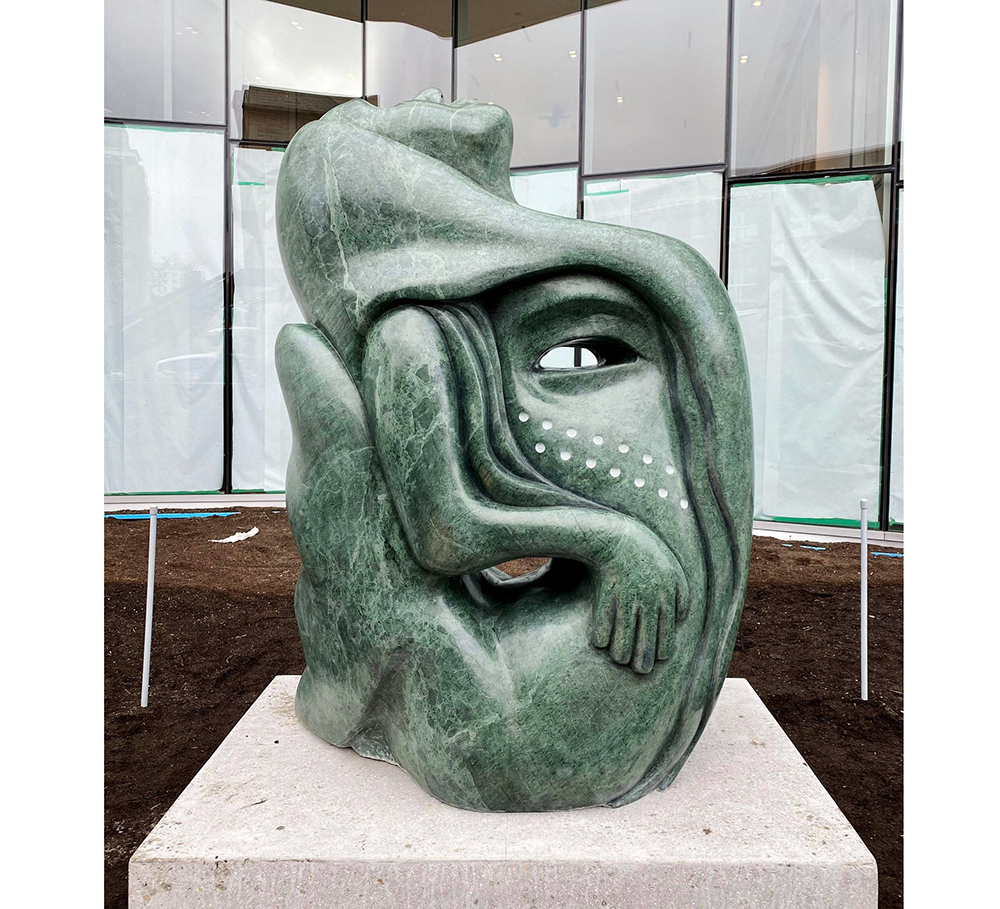

After nearly two years in progress, the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG) unveiled a 9,072 kilogram (approximately 10 tonne) stone sculpture by Goota Ashoona in front of Qaumajuq on January 21st. It is the first of several public-art pieces to be unveiled in front of the new building and was supported by the Manitoba Teachers’ Society. The only Inuit art museum in North America, Qaumajuq is set to open to the public later this year.

Standing over seven feet tall and four feet around, Tuniigusiia/The Gift is made from Guatemalan Verdant, a dark, jade-like green stone with lighter veins. “I chose that green colour because my parents used to carve that colour and it was beautiful,” says Ashoona when reached by phone from her farm just outside Winnipeg, MB.

It wasn’t easy to source a piece of stone large enough for this massive public-art project, she continues. There are no commercial quarries in North America producing serpentinite—one of the main stones historically quarried and carved by Inuit artists like Kiugak Ashoona and Sorroseeleetu Ashoona, Goota’s parents—large enough to meet the artist’s requirements, so they sourced this piece of Guatemalan Verdant from India and had it shipped to Canada specially for the project.

“This is the biggest one that I dreamed of, that I’ve been wanting to do...even before I started carving,” says Ashoona. Not only is this new work the largest sculpture ever created by the artist, but one of the biggest created by any member of the Ashoona family. As far as Ashoona is aware, it is one of the biggest sculptures ever created by any Inuit artist, ever.

Feeling a strong personal connection to the WAG—stemming from the amount of artwork in the WAG vaults that was made by her family—Ashoona wanted a personal subject to match. “I chose the mermaid because I heard about it from my grandmother when she told the story, or my mother,” says Ashoona, adding that there are stories about mermaids “pretty much everywhere” back home, often referencing Nuliajuk (Sedna).

The mermaid’s tale curves around the profiles of a mask on one side and a mother teaching her daughter how to throat sing on the other, mimetically representing the same intergenerational knowledge transfer that inspired the mermaid itself, and the role teachers play in communities.

Continue reading at Inuit Art Foundation.