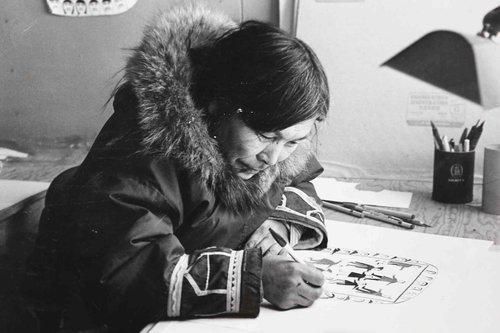

Undated photo in Baker Lake September 24, 2016

Oonark was born in 1906 near the Haningayok (Back River), Nunavut, an area known as the Barren Lands. She lived nomadically for the first 50 years of her life, involved in traditional pursuits such as processing and sewing animal hides to make clothing. These tasks would inform the subject and style of later artwork as well as instill a prodigious work ethic.

In the 1950s, a decline in both caribou populations and the market for pelts caused a famine among her people. Oonark lost her husband and four of her twelve children to starvation. Along with hundreds of Inuit, Oonark and her family were relocated by the Canadian government to a permanent settlement in Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake) in 1958. To support herself and her children, she worked various odd jobs including sewing, cooking and cleaning.

Oonark had never made drawings before moving to Baker Lake at the age of 52. The story goes that Oonark saw some illustrations made by children and proclaimed that she could easily do better herself, and picked up the tools to prove it. Dr. Andrew Macpherson, a visiting biologist, saw the resulting drawings, and gave Oonark more materials. Over the ensuing years, the two swapped art supplies for art. Self-taught, her work also attracted the notice of members in both the Qamani’tuaq and Kinngait (Cape Dorset) artistic communities, giving her the opportunity to work with printmakers in both settlements. This is especially notable given that she did not live in Kinngait, and was the first non-resident to be accorded the privilege.

Oonark was given a small studio and a stipend, allowing her to devote more of her time to creation. Wildly prolific and dedicated to her work, at times her output was around forty to fifty drawings per week, more than 100 of which were translated into prints for the annual Sanavik Cooperative Baker Lake Print Catalogue between 1970 and 1985. Her son, the artist William Noah, remembers her always working, at a loss to recall what his mother did for fun. He recalls that “there was always that determination to do every task to the very best of her abilities, and she told us we must do the same.”

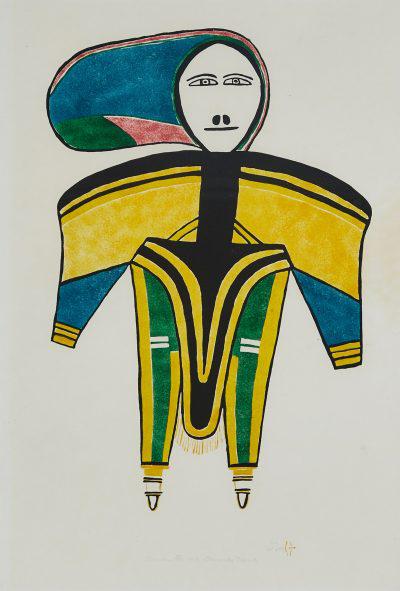

One of Oonark’s most recognizable images is a stonecut made in 1974, Big Woman. Highly sought after, one print from this edition of 50 is held in the National Gallery of Canada’s permanent collection. Another was offered in Waddington's Inuit Art auction.

The titular Big Woman showcases the cultural attributes associated with an Inuit woman: the traditional facial tattoos, the curved ulu knife, and a complexly-made amautiq or women’s parka. Oonark rendered her protagonist in dazzling colours and geometric patterns, which echo the lines of the facial tattoos. The ulus, a recurring motif in the artist’s work, emerge from her head like plumage. The Inuit Art Foundation explains that Oonark, known for her poetic speech, said that her work represented her dreams, and Big Woman combines the realities of Inuit life with a dream-like world of the artist’s imagining.

THE STRENGTH, IMPORTANCE AND POWER OF INUIT WOMEN

Often, Oonark’s work centers around the strength, importance and power of Inuit women. Bold designs and vivid colours characterize her work, which references the life, work, myth and culture of the Inuit people. Robert Enright writes of “the whimsical, awkward gestures [Oonark’s] figures make,” noting that, “the colours in the drawings speak unequivocally about Oonark’s uncompromising celebration of Inuit life.” Indeed, the superbly graphic quality of the artist’s work is perhaps what sets her work apart, reflecting a deeply intuitive understanding of composition, colour, symmetry and pattern.

In Big Woman (1974), Woman(1970), and Big Woman (1976), Oonark’s figures wear vibrant outfits, isolated against an empty ground. Woman even seems to float weightlessly, her toes pointed downwards, away from her body, clad in boots so tiny they appear doll-like. Flat planes of colour are employed to great effect, and can sometimes border on abstraction. Like all great artists, Oonark allows for multiple points of entry into her work, leaving enough ambiguity for the viewer to have room to explore, to construct their own narratives.

Oonark herself was no stickler for narrative, explaining that, while inspired by a story for “Big Woman”, she altered the drawing to suit herself. Oonark described “this woman who is turning into a stone, in Chantrey Inlet. The stone itself is really colourful because this woman has a fancy parka… She turned into stone… because she never wanted to get married to anybody, not anyone at all. The woman is supposed to be in a kneeling position, but I just drew it in a standing position anyway.”

Oonark’s images are often deceptively simple, reduced to essentials. Sarah Milroy notes the artist’s use of “often dramatic dislocations of scale in the service of emphasis—an approach unfamiliar to European eyes accustomed to three-point perspective. In Oonark’s world, scale speaks not of foreground proximity but of importance…the whole is understood, with Oonark indulging an emphatic pictorial shorthand that is all the more expressive for its economy.” Accordingly, we can read Oonark’s Women as vital forces, larger than life in terms of both scale and importance.