Nivingajuliat: Inuit Wall Hangings

Waddington's | April 6, 2023

Categories:

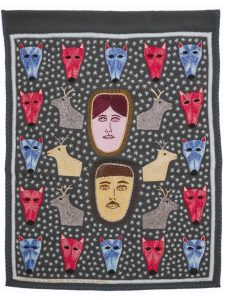

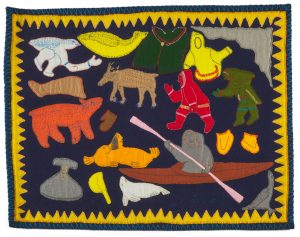

In the late 1960s, a small group of Inuit women in Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), Nunavut, began creating a new artform: nivingajuliat or wall hangings. The artform emerged as an unintended result of government-sponsored arts and craft programs. Spurred by economic necessity, the seamstresses of Qamani’tuaq began using scraps of fabric to make appliquéd images, harnessing their traditional sewing skills to make contemporary textile-based art that has attracted the notice of major museums, collectors and international audiences. Not just aesthetically pleasing, nivingajuliat have become an important reservoir of Inuit culture: preserving ancestral sewing skills, amplifying women’s voices, and recording legends, oral histories, and a disappearing way of life.

SEWING TO SURVIVE

Before the 1950s, the Inuit lived a nomadic lifestyle. Men were responsible for hunting and fishing, creating tools from hide, bone, stone and wood. Women processed meat and hides, using needles made of bone and antler to make warm, waterproof clothing and tents to equip their families against the harsh Arctic climate.

An accomplished seamstress was highly respected in traditional Inuit communities, and sewing was viewed as an important survival skill. Passed down from generation to generation, working with a needle was one of the first skills taught to young children. Artist Ruth Qaulluaryuk recalls her mother’s insistence on her learning proper stitchcraft. She warned her that without this skillset, she faced the prospect of freezing to death: other women would not have the time to make clothing and coverings for her, occupied as they were with their own domestic tasks and familial requirements.

Though function was the highest priority when constructing clothing, Inuit women found a way to elevate their tasks into an expressive personal artform. Well-prepared hides and furs were matched for colour, texture and tone. When constructing an amauti – the parka worn by Inuit women – makers would piece together contrasting bands of fur to form decorative patterns, highlighting elements of their designs. When contact was made with European traders, beads entered the local economy, and began to find their way onto Inuit clothing, carefully sewn in decorative fringes and appliqués.

By the 1950s, changing caribou migration patterns and new government policies forced many Inuit to abandon their nomadic lifestyle and resettle into static communities like Qamani’tuaq. For the first time, separated from the land, the Inuit became dependant on a cash economy in order to survive – but without adequate prospects to earn money. Compounding the problem was the sinking price and declining demand for fur— one of the few goods the Inuit were able to sell for profit.

Government relief was introduced, as were programs that might help supplement the incomes of Inuit communities. Some of the more viable included arts and crafts programs. By the late 1940s, Inuit art began to attract interest from southern Canadian audiences, with drawing, printmaking and sculpture at the forefront of this new cultural wave. Nivingajuliat, which would become a signature medium for Qamani’tuaq, took a little longer to emerge—and certainly to be recognized.

TRANSFORMING TRADITION

In the 1960s, a government-sponsored craft program was established in Qamani’tuaq under the supervision of Gabriel Gély. By the mid-1960s, women were participating in sewing initiatives organized by Elizabeth Whitton, the wife of an Anglican minister stationed there. Whitton envisioned a cottage industry of clothing manufacture, whereby women could use their traditional sewing skills to earn money in the wage economy. Whitton introduced dressmaking, as well as providing wool duffle to make mitts and socks for export to southern markets.

Among the women included in these initiatives were Jessie Oonark and her cousin Marion Tuu’luq. They began using the scraps left over from the government project to create small stitched and appliquéd pictures. Oonark and Tuu’luq were soon joined by others, including Victoria Mamnguqsualuk and Naomi Ityi.

These small pictures attracted the interest of Jack and Sheila Butler, who had arrived in Qamani’tuaq in 1969 as craft officers, tasked with establishing a printmaking program.

They began purchasing the fabric works, as well as providing the women with better materials to work with. Soon, duffle, stroud, felt, and a wide range of embroidery floss were included in the annual shipment of government-funded art supplies. Improved materials allowed the women to make larger and more complex images, which they worked on during spare time, at home, and even while out on the land during summer hunts.

Though nivingajuliat record the voices and interests of their creators, they were not originally made for Inuit audiences. Of her work, Tuu’luq explained that: “I created what I thought people would like.” No longer a tool necessary for physical survival, skill with a needle became a tool that could be harnessed for financial survival, and production of commercially-driven nivingajuliat ramped up in the early 1970s.

Artists relied on the sale of these works to feed their families, and were curious as to what audiences in southern Canada might want to buy. Accordingly, they would solicit the opinions and suggestions of the white people living among them: government employees stationed there to run the arts initiatives, RCMP officers, missionaries, teachers and traders. Curator Marie Routledge notes that strong language barriers between Inuktitut and English speakers meant that feedback was often vague. In her words, “the message was most effectively communicated through the amount of money exchanged between parties.”

WOMEN’S VOICES

So-called “female” mediums like sewing, embroidery, and weaving have long been undervalued and often dismissed by Western culture. Inuit art was no exception when viewed through a Eurocentric lens: sculpture and works on paper, more easily aligned with the hierarchy of the Western canon, have typically been seen to define the artistic history of the region. As textile art has long been categorized as craft, this hindered the recognition of the artistic merit of nivingajulait in non-Inuit contexts. Crucially, this value-laden distinction between art and craft is not upheld within Inuit culture, which understood the intrinsic power, function and necessity of women’s work. Routledge makes the argument that even the English translation of nivingajuliat, “wall hangings” does them a disservice, preferring to refer to them as works on cloth.

Art stimulated the Arctic economy, while also introducing new forms of self-expression. Whitton wrote that “many people were fascinated by being able to express old legends, scenes from their way of life, in various media.” Art historian Marie Bouchard writes that “while no one was anxious to return to the hardships of traditional life, Inuit nonetheless recognized the opportunity to use introduced art-making techniques to remember and memorialize their past, to “hold on” to it as long as they could in order to thwart cultural erasure. Knowledge of caribou-skin clothing design and construction, a heightened aesthetic awareness of organic shapes and forms, and refined sewing techniques all played an important role in providing the underlying organizational structure for creating images on cloth.”

Nivingajuliat enabled women to document their stories and memories, both personal and communal, narratives which might otherwise be excluded from the narrative of Arctic history. Pre-contact, Inuit culture was a largely oral tradition, and the introduction of the graphic arts allowed for a new form of recording. In the words of Irene Avaalaaqiaq:

“Whenever I see my wall hangings they remind me of my life. Also I always remember my grandmother and the stories and legends she told me. When I grew up there were no other people except my grandparents. I had never seen white people. When I do sewing and make a wall hanging I do what I remember. I can see it clear as a picture. When I am looking at it, it looks like it is actually happening in those days, as it was in my life.”

It comes as no surprise that each artist found her own style, not only in terms of subject and composition but in the stitches themselves. The trailblazing women who defined the form had little or no formal training in embroidery, borrowing techniques from each other and making up stitches as required—some even creating easily identified “signature” stitches. Whitton made it clear that “the stitches have not been taught from an outside source, or learned from any manual on stitchcraft. Each individual has evolved her own to express the idea she is creating.” The arts and crafts officers encouraged each artist to pursue her own path, which echoed traditional Inuit custom that each woman should interpret and personalize her work as she saw fit, drawing from her toolbox of core skills.

MATERIALS AND METHOD:

Most nivingajuliat are made with similar materials stitched together with embroidery floss – duffle, stroud, and felt. These textiles had been present in Arctic communities before the first instances of nivingajuliat. Their sturdiness and non-raveling properties lent themselves to traditional sewing techniques. The basic method of making nivingajuliat is referred to as appliqué, a process whereby pieces or patches of fabric are sewn or fixed onto a larger support. With nivingajuliat, forms are often cut out freehand, and typically reference animals, traditional activities and beliefs, legends, shamanic figures, and personal stories. A defining feature of nivingajuliat from Qamani’tuaq is embroidery, as artists embellish their work to add great subtlety, movement, and depth of colour to their compositions. Stroud, duffel and felt typically come in a narrow range of hues, while a wider range of coloured embroidery thread layered onto these hues allowed women to achieve intermediate shades.

The back or verso of nivingajuliat vary between artists, but many, like Tuu’luuq, pride themselves on the tidy appearance of the reverse, which they consider the mark of a talented seamstress. A traditional Inuit stitch involves passing the needle only partway through the material at hand—a technique which allows seamstresses to create waterproof garments—which has been transposed onto the making of nivingajuliat.

Here’s what you need to know about the materials used:

DUFFLE: Deriving its name from the Belgian town of Duffel, this material is a tightly woven, heavy-weight woollen cloth with a thick coarse texture (known as nap) on both sides. Dating back at least to the 1600s, it was used to make warm, weather-resistant clothing – hence, the duffle coat. Imported to the Arctic by traders, Inuit began incorporating it into their traditional clothing, using it to line parkas. Duffle traditionally forms the background for nivingajuliat.

STROUD: Sourcing its name from the English town where it was made, stroud is also a woolen cloth with a dense nap, though is thinner and less expensive to produce. Sating back to the 1600s, stroud was first made by processing woollen rags, and was designed for trade with the Indigenous population of North America. Like duffle, stroud is suitable for use as the background for nivingajuliat.

FELT: Unlike the previous two materials, felt is not woven. Felt is made by combining wool with a sizing liquid before it is pressed and rolled into thin fabric sheets. Felt can also be made with fur or hair, using the same process. The resulting material does not fray when it is cut, making it ideal for use in appliqué.

ABOUT THE AUCTION

Waddington’s is pleased to present Nivingajuliat: Inuit Wall Hangings, online from April 22-27, 2023.

On View:

Sunday, April 23 from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm

Monday, April 24 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Tuesday, April 25 from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Note: This auction starts to close at 3 pm ET.

Please contact us for more information.